A person's chance of surviving cardiac arrest is significantly higher if a bystander calls 911 and applies chest compressions.

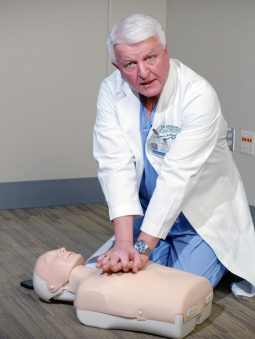

In a hospital conference room, Dr. Peter Kudenchuk is on his knees as he demonstrates forceful chest compressions on “Annie,” a CPR manikin. “One and two and three and four,” he calls out repeatedly, maintaining a cadence of 100 to 120 beats per minute.

Kudenchuk, a UW Medicine cardiologist, has long studied cardiac arrest and its survival. He has watched with interest this the past month as public attention increased toward automated external defibrillators (AEDs), instruments that can revive people who experience cardiac arrest, like NFL player Damar Hamlin.

He also knows that most bystander-witnessed cardiac arrests occur in the home, on a sidewalk or at some other venue where no AED is nearby, or known to be.

In that moment, though, there’s still an opportunity for someone to take action that could help save a life.

“The first thing to do is establish whether the person who's fallen is arousable. Shake them; if you can’t arouse them, call 911 right away. And if the person is also not breathing normally, start chest compressions. On the other hand, if they're awake and complaining of chest discomfort, that also requires a 911 call, but not CPR,” Kudenchuk said, differentiating the electrical malfunction of cardiac arrest, which causes sudden collapse, and a blocked heart artery that causes chest pain.

While each of these can be called a “heart attack,” a cardiac arrest is the more ominous emergency that requires immediate CPR.

During cardiac arrest, the normal heartbeat is interrupted by a dangerous rhythm that halts circulation. Chest compressions may not get the person’s heart beating again, but they buy time until medical responders arrive. And until professional help arrives, doing chest compressions alone is sufficient CPR; you don’t need to add rescue breathing, Kudenchuk clarified.

“Chest compressions take advantage of the chest as a pump. Immediately after a collapse there’s still oxygen and blood in the chest, in the lungs, and in the heart. When you press on the chest, you’re pushing that blood out into the brain and other vital organs. And what you are doing, multiple studies have shown, is forestalling death” until other treatments, like a life-saving shock can be delivered, said Kudenchuk. He is also medical director for the King County Medic One emergency-response program.

If you might hesitate to deliver CPR — for fear of injuring the victim or heightening your own risk to a disease like COVID-19 — consider this: Nationally, just 1 in 10 people who experiences an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survives. Bystander-delivered chest compressions can improve those numbers by two to three times.

“With chest compressions alone, you’re going to double or triple the odds of that person surviving the event,” Kudenchuk said. “If you’re just doing chest compressions without mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, even if the person has something infectious, you're not going to contract that. Second, doing CPR is not harmful. The chance of significant injury is minimal. If the person wakes up and didn’t actually need CPR, they will just push you away.

“Even if you don't do CPR perfectly, you're giving that patient an opportunity for a life they might otherwise never have.”

SOURCE: Brian Donohue, University of Washington