A drone network could be deployed to speed defibrillators to bystanders trying to help people in cardiac arrest, getting the devices to the patient faster than emergency services, a recent Canadian study suggests.

Researchers examined historical data on 53,702 cardiac arrests over 26,851 square kilometers (10,367 square miles) of rural and urban regions surrounding Toronto, Ontario, to see how drones might be deployed to get help to cardiac arrest patients more quickly than typical 911 response times.

If drones were spread evenly across the region, researchers calculated that it would require 37 drones spread across 23 bases to get patients started on defibrillator treatment about one minute faster than they would have been if they waited for emergency services.

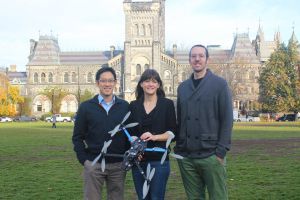

“Because the drone can fly in a straight line, potentially avoiding obstacles that the ambulance cannot, the drone can arrive to scene more quickly and be carrying a defibrillator that a bystander can use before the paramedics arrive,” said Timothy Chan, director of the Center for Healthcare Engineering at the University of Toronto.

“Paramedics can take over after they arrive, but because survival from cardiac arrest is so time sensitive, even defibrillating the patient a minute before paramedics get there can make a huge difference,” Chan said by email.

By concentrating more drones in urban areas instead, it would require 28 drones on 15 bases to get aid to the patients an average of one minute faster, researchers report in Circulation.

In their simulations, drones in the most urban areas yielded a best time savings of 6 minutes 43 seconds, and in the most rural areas, the best clocked times got the drone to the patient 10 minutes and 34 seconds sooner than historical 911 response times.

In cardiac arrest, the heart stops abruptly, often due to irregular heart rhythms. Cardiac arrest may occur with no warning and is often fatal unless the heart can be restarted quickly.

Automated defibrillators are already common in public places like restaurants and airports. These devices typically have electrodes that attach to the chest with sticky pads and deliver shocks based on what a computer in the defibrillator determines the person needs.

Several companies and researchers have developed prototype drone technology that might be used to deliver defibrillators to the scene of a cardiac arrest, researchers note. Google, for example, has a patent for drone delivery of defibrillators and other medical supplies, and companies have also proposed using drones to deliver everything from pizza to official documents.

In the study, researchers calculated that a regional network of 100 drones on 80 bases would be needed to reduce the time it takes to start defibrillators by three minutes. If they concentrated drones in areas with the most people, they would need 70 drones on 49 bases.

If they could get drones to beat 911 times by 3 minutes, 92 percent of cardiac arrest patients would be treated faster under a drone system than they would be by relying on the typical emergency medical services network, the researchers conclude.

One limitation of the study is that researchers used data only on confirmed cardiac arrest cases, not every suspected cardiac arrest called in to 911 dispatchers, the authors note. This might mean they underestimated the number of drones needed, because they would still need to be deployed on calls that turned out to be false alarms.

Another drawback of the study is it doesn’t calculate costs, which the authors note might be considerable.

An effective drone delivery network would also require a massive public education effort to make sure enough bystanders know how to use the defibrillators, said Dr. Peter Pons, a professor emeritus of emergency medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine who wasn’t involved in the study.

“This concept is in its infancy but there have been some initial efforts in this regard,” Pons said by email.

Drones were used to deliver small aid packages in Haiti after the earthquake, Pons said. They have also been used in a trial situation to fly laboratory test specimens from a remote location to an urban testing lab.

SOURCE: Lisa Rapaport, Reuters Health